ANOREXIA, BULIMIA and THE MINNESOTA STARVATION EXPERIMENT

Starvation experiment participant Sam Legg

There are striking parallels between victims of semi-starvation/starvation and those who suffer from bulimia and/or anorexia nervosa.

There are striking parallels between victims of semi-starvation/starvation and those who suffer from bulimia and/or anorexia nervosa.

Physiologist Ancel Keys led the starvation experiment

Probably

the most systematic study of the effects of starvation was conducted

over 30years ago by Ancel Keys and his colleagues at the University of

Minnesota (Keys, Brozek, Henschel, Mickelsen & Taylor, 1950). The

experiment, commonly referred to as the Minnesota Starvation Experiment/Study,

involved restricting the caloric intake of 36 young, healthy,

psychologically normal men who had volunteered for the study as an

alternative to military service.

During the first three months of

the experiment, the men ate normally, while their behavior,

personality, and eating patterns were studied in detail. During the

subsequent six months, the men were restricted to approximately half of

their former food intake and lost, on average, 25% of their original

body weight. This was followed by three months of rehabilitation, during

which time the men were gradually re-fed.

Although their

individual responses varied considerably, the men experienced dramatic

physical, psychological, and social changes as a result of the

starvation. In most cases, these changes persisted during the

rehabilitation or re-nourishment phase.

An inevitable result of

starvation was a dramatic increase in preoccupation with food. The men

found concentration on their usual activities increasingly difficult,

since they were plagued by persistent thoughts of food and eating. In

fact, food became a principal topic of conversation, reading, and

daydreams. Many of the men began reading cookbooks and collecting

recipes.

Starvation subjects became overwelmingly preocupied with food.

Some collected dozens of cookbooks

Some

developed a sudden interest in collecting coffee-pots, hot plates, and

other kitchen utensils. This hoarding even extended to non-food-related

items:

Some of the men collected old books, unnecessary

second-hand clothes, knick knacks, and other "junk." Often after making

such purchases, which could be afforded only with sacrifice, the men

would be puzzled as to why they had bought such, more or less, useless

articles. (Keys et al., 1950, p. 837)

One man even began

rummaging through garbage cans with the hope of finding something that

he might need. This general tendency to hoard has been observed in

starved anorexic patients (Crisp, Hsu, & Harding, 1980) and even in rats deprived of food (Fantino & Cabanac, 1980).

Despite

little interest in culinary matters prior to the experiment, almost 40%

of the men mentioned cooking as part of their post-experiment plans.

For some, the fascination was so great that they actually changed

occupations after the experiment: three became chefs, and one went into

agriculture.

During starvation, the volunteers' eating habits

underwent remarkable changes. The men spent much of the day planning how

they would eat their allotment of food. Much of their behavior served

the purpose of prolonging the ingestion and hedonic appeal or saliency

of food. The men often ate in silence and devoted total attention to

consumption.

The

Minnesota subjects were often caught between conflicting desires to

gulp their food down ravenously and consume it slowly so that the taste

and odour of each morsel would be fully appreciated. Toward the end of

starvation, some of the men would dawdle for almost two hours over a

meal which previously they would have consumed in a matter of minutes.

(Keys et al.,1950, p. 833)

The men demanded that their food be

served hot, and they made unusual concoctions by mixing foods together.

There was a tremendous increase in the use of salt and spices. The

consumption of coffee and tea increased so dramatically that the men had

to be limited to 9 cups per day; similarly, gum chewing became

excessive and had to be limited after it was discovered that one man was

chewing as many as 40 packages a day.

During the 12-week

rehabilitation phase, most of these attitudes and behaviors persisted.

For a small number of men, these became even more marked during the

first six weeks of refeeding:

In many cases the men were not

content to eat "normal" menus but persevered in their habits of making

fantastic concoctions and combinations. The free choice of ingredients,

moreover, stimulated "creative" and "experimental" playing with food,

licking of plates, and neglect of table manners persisted. (Keys et al.,

1950, p. 843)

Bulimia

During the

starvation regimen, all of the volunteers reported increased hunger;

some appeared able to tolerate the experience fairly well, but for

others it created intense concern, or even became intolerable. Several

men failed to adhere to their diets and reported episodes of bulimia followed

by self-reproach. While working in a grocery store, one subject

suffered a complete loss of willpower and ate several cookies, a sack of

popcorn, and two overripe bananas before he could "regain control" of

himself. He immediately suffered a severe emotional upset, with nausea,

and upon returning to the laboratory he vomited. He was

self-deprecatory, expressing disgust and self-criticism. (Keys et al.,

1950,p. 887)

During the eighth week of starvation, another subject "flagrantly

broke the dietary rules, eating several sundaes and malted milks; he

even stole some penny candies. He promptly confessed the whole episode,

[and] became self-deprecatory" (Keys et al.,1950, p. 884).

When

presented with greater amounts of food during rehabilitation, many of

the men lost control of their appetites and "ate more or less

continuously" (Keys et al., 1950, p. 843). Even after 12 weeks of

rehabilitation, the men frequently complained that they experienced an

increase in hunger immediately following a large meal:

[One

of the volunteers] ate immense meals (a daily estimate of 5,000 to

6,000 calories) and yet started snacking" an hour after he finished a

meal. [Another] ate as much as he could hold during the three regular

meals and ate snacks in the morning, afternoon and evening. (Keys et al., 1950, p. 846)

This

gluttony resulted in a high incidence of headaches, gastrointestinal

distress and unusual sleepiness. Several men had spells of nausea and

vomiting. One man required aspiration and hospitalization for several

days. (Keys et at., 1950, p. 843)

There

were weekend "splurges" in which intake commonly ranged between 8,000

and 10,000 calories. The men frequently found it difficult to stop

eating:

"Subject

No. 20 stuffs himself until he is bursting at the seams, to the point

of being nearly sick and still feels hungry; No. 120 reported that he

had to discipline himself to keep from eating so much as to become ill;

No. 1 ate until he was uncomfortably full; and subject no. 30 had so

little control over the mechanics of "piling it in" that he simply had

to stay away from food because he could not find a point of satiation

even when he was "full to the gills." . . . Subject no. 26 would just as

soon have eaten six meals instead of three." (Keys et al., 1950, p. 847)

After

about five months of rehabilitation, the majority of the men reported

some normalization of their eating patterns; however, for some the

extreme overconsumption persisted: "No. 108 would eat and eat until he could hardly swallow any more, and then he felt like eating half an hour later" (Keys et al., 1950, p. 847).

More than 8 months after renourishment, a few men were still eating abnormal amounts, and one man still reported consuming "about 25 per cent more than his pre-starvation amount; once he started to reduce but got so hungry he could not stand it" (Keys et al., 1950, p. 847).

Factors

that distinguished men who rapidly normalized their eating from those

who continued to eat prodigious amounts were not identified. However,

the important point here is that there were tremendous differences among

volunteers in their responses to the starvation experience, and that a

subset of these men developed bulimia, which persisted many months after they were permitted free access to food.

Emotional Changes

The

strict procedures used to select subjects for the experiment led the

experimenters to conclude that the "psychobiological 'stamina' of the

subjects was unquestionably superior to that likely to be found in any

random or more generally representative sample of the population" (Keys

et al., 1950, p. 916). Although the subjects were psychologically

healthy prior to the experiment, most experienced significant emotional

changes as a result of semi-starvation. Some reported transitory and

others protracted periods of depression, with an overall lowering of the

threshold for depression. Occasionally elation was observed, but this

was inevitably followed by "low periods." Although the men had quite

tolerant dispositions prior to starvation, tolerance was replaced by

irritability and frequent outbursts of anger. For most subjects, anxiety

became more evident.

As the experiment progressed, many of the

formerly even-tempered men began biting their nails or smoking because

they felt nervous. Apathy became common, and some men who had been quite

fastidious neglected various aspects of personal hygiene. Most of the

subjects experienced periods during which their emotional distress was

quite severe, and all exhibited the symptoms of "semi-starvation

neurosis" described above.

Almost 20% of the group experienced

extreme emotional deterioration that markedly interfered with their

functioning. Standardized personality testing with the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)

revealed that semi-starvation resulted in significant increases in

depression, hysteria, and hypochondriasis for the group. This profile

has been referred to as the "neurotic triad" and is observed among

different groups of neurotically disturbed individuals (Greene, 1980).

These emotional aberrations did not vanish immediately during

rehabilitation, but persisted for several weeks, with some men actually

becoming more depressed, irritable, argumentative, and negativistic than

they had been during semi-starvation.

During semi-starvation two

subjects developed disturbances of "psychotic" proportions. One of

these was unable to adhere to the diet and developed alarming symptoms:

"[He

exhibited] a compulsive attraction to [garbage] and a strong, almost

compelling, desire to root in garbage cans [for food to eat]. He

repeatedly went through the cycle of eating tremendous quantities of

food, becoming sick, and then starting all over again [and) became

emotionally disturbed enough to seek admission voluntarily to the

psychiatric ward of the University Hospitals." (Keys et al., 1950, p. 890)

After nine weeks of starvation, another subject exhibited signs of disturbance:

"[He

went on a] spree of shoplifting, stealing trinkets that had little or

no intrinsic value. He developed a violent emotional outburst with

flight of ideas, weeping, talk of suicide and threats of violence.

Because of the alarming nature of his symptoms, he was released from the

experiment and admitted to the psychiatric ward of the University

Hospitals." (Keys et al., 1950, p. 885)

Another man chopped off three fingers of one hand in response to stress.

For a few volunteers, mood swings were extreme:

"[One

subject] experienced a number of periods in which his spirits were

definitely high. These elated periods alternated with times in which he

suffered "a deep dark depression." [He] felt that he had reached the end

of his rope [and] expressed the fear that he was going crazy [and]

losing his inhibitions." (Keys et al., 1950, p. 903)

Personality

testing (with the MMPI) of a small minority of subjects confirmed the

clinical impression of incredible deterioration as a result of

semi-starvation. "...one

man's personality profile [was] initially...well within normal limits,

but after 10 weeks of semi-starvation and a weight loss of only about

4.5 kg (10 lb, or approximately 7% of his original body weight), gross

personality disturbances were evident." On the second

testing, all of the MMPI scales were elevated, with severe personality

disturbance on the scales for neurosis as well as those for psychosis.

Depression and general disorganization were particularly striking

consequences of starvation for several of the men who became the most

emotionally disturbed.

It may be concluded from clinical

observation as well as standardized personality testing that the

individual emotional response to semi-starvation conditions varies

considerably. Some of the volunteers in Keys et al.'s experiment seemed

to cope relatively well, and others displayed extraordinary disturbance

following weight loss. The type of disturbance was quite similar to that

described in obese individuals exposed to "therapeutic" semi-starvation

(Glucksmaii & Hirsch, 1969; Rowland, 1970).

In the Minnesota

experiment, pre-starvation personality adjustment did not predict the

emotional response to caloric restriction. Some of the men who appeared

to be the most stable reacted with severe disturbance. The fact that

people respond so differently and unpredictably to weight loss is

clearly relevant to an assessment of those who have dieted below their

optimal weight.

Since the emotional difficulties in the Minnesota

volunteers did not immediately reverse themselves during

rehabilitation, it may be assumed that the abnormalities were related

more to body weight than to short-term caloric intake. It may be

concluded that many of the psychological disturbances found in anorexia nervosa and bulimia may be the result of the semistarvation process.

Social and Sexual Changes

The

extraordinary impact of semi-starvation is reflected in the social

changes experienced by most of the volunteers. Although originally quite

gregarious, the men became progressively more withdrawn and isolated.

Humour and the sense of comradeship diminished markedly amidst growing

feelings of social inadequacy:

Social initiative especially, and

sociability in general, underwent a remarkable change. The men became

reluctant to plan activities, to make decisions, and to participate in

group activities. They spent more and more time alone. It became "too

much trouble" or "too tiring" to have contact with other people. (Keys

et al., 1950, pp. 836-837)

The volunteers' social contacts with

women also declined sharply during semi-starvation. Those who continued

to see women socially found that the relationships became strained.

These changes are illustrated in the description from one man's diary:

"I

am one of about three or four who still go out with girls. I fell in

love with a girl during the control period but I see her only

occasionally now. It's almost too much trouble to see her even when she

visits me in the lab. It requires effort to hold her hand. Entertainment

must be tame. If we see a show, the most interesting part of it is

contained in scenes where people are eating." (Keys et al., 1950, p. 853)

Sexual

interests were likewise drastically reduced. Masturbation, sexual

fantasies, and sexual impulses either ceased or became much less common.

One subject graphically stated that he had "no more sexual feeling than a sick oyster." (Even this peculiar metaphor made reference to food.) The investigators observed that "many of the men welcomed the freedom from sexual tensions and frustrations normally present in young adult men" (Keys et al., 1950, p. 840).

The

fact that starvation perceptibly altered sexual urges and associated

conflicts is of particular interest, since it has been hypothesized that

this process is the driving force behind the dieting of many anorexia nervosa patients. According to Crisp (1980), anorexia nervosa is an adaptive disorder in the sense that it curtails sexual concerns for which the adolescent feels unprepared.

During

rehabilitation, sexual interest was slow to return. Even after three

months, the men judged themselves to be far from normal in this area.

However, after eight months of re-nourishment, virtually all of the men

had recovered their interest in sex.

Cognitive Changes

The

volunteers reported impaired concentration, alertness, comprehension,

and judgment during semi-starvation; however, formal intellectual

testing revealed no signs of diminished intellectual abilities.

Physical Changes

As

the six months of semi-starvation progressed, the volunteers exhibited

many physical changes, including the following: gastrointestinal

discomfort, decreased need for sleep, dizziness, headaches,

hypersensitivity to noise and light, reduced strength, poor motor

control, edema (an excess of fluid causing swelling), hair loss,

decreased tolerance for cold temperatures (cold hands and feet), visual

disturbances (i.e. inability to focus, eye aches, "spots" in the visual

fields), auditory disturbances (i.e. ringing noise in the ears), and

paresthesia (i.e. abnormal tingling or prickling sensations, especially

in the hands or feet).

Various changes reflected an overall

slowing of the body's physiological processes. There were decreases in

body temperature, heart rate, and respiration, as well as in basal

metabolic rate (BMR). BMR is the amount of energy (calories) that the

body requires at rest (i.e. no physical activity) in order to carry out

normal physiological processes. It accounts for about two-thirds of the

body's total energy needs, with the remainder being used during physical

activity. At the end of semi-starvation, the men's BMRs had dropped by

about 40% from normal. This drop, as well as other physical changes,

reflects the body's extraordinary ability to adapt to low caloric intake

by reducing its need for energy. One volunteer described that it was as

if his "body flame [were] burning as low as possible to conserve precious fuel and still maintain life process" (Keys et al., 1950, p. 852).

During

rehabilitation, metabolism again speeded up, with those consuming the

greatest number of calories experiencing the largest rise in BMR. The

group of volunteers who received a relatively small increment in

calories during rehabilitation (400 calories more than during

semi-starvation) had no rise in BMR for the first three weeks. Consuming

larger amounts of food caused a sharp increase in the energy burned

through metabolic processes.

The changes in body fat and muscle

in relation to overall body weight during semi-starvation and

rehabilitation are of considerable interest. While weight declined about 25%, the percentage of body fat fell almost 70%, and muscle decreased about 40%. Upon

re-feeding, a greater proportion of the "new weight" was fat; in the

eighth month of rehabilitation, the volunteers were at about 100% of

their original body weight, but had approximately 140% of their original body fat! How did the men feel about their weight gain during rehabilitation?

Those

subjects who gained the most weight became concerned about their

increased sluggishness, general flabbiness, and the tendency of fat to

accumulate in the abdomen and buttocks. (Keys et al., 1950, p. 828)

A page of Harold Blickenstaff's diary during his participation in the starvation experiment.

Here, Blickenstaff tracks his weight loss

These complaints are similar to those of many bulimic and anorexic

patients as they gain weight. Besides their typical fear of weight

gain, they often report "feeling fat" and are worried about acquiring

distended stomachs. However, the body weight and relative body fat of

the Minnesota volunteers had begun to approach the pre-experiment levels

after just over a year.

Physical Activity

In

general, the men responded to semi-starvation with reduced physical

activity. They became tired, weak, listless, and apathetic, and

complained of lack of energy. Voluntary movements became noticeably

slower. However, according to the original report,

"...some

men exercised deliberately at times. Some of them attempted to lose

weight by driving themselves through periods of excessive expenditure of

energy in order either to obtain increased bread rations or to avoid

reduction in rations." (Keys et al., 1950, p. 828)

Starvation experiment participants on the treadmill

This is similar to the practice of some anorexic and bulimic

patients, who feel that if they exercise strenuously, they can allow

themselves a bit more to eat. The difference is that for the patients

the caloric limitations are self-imposed.

Significance of the Starvation Study

As

is readily apparent from the preceding description of the Minnesota

experiment, many of the symptoms that might have been thought to be

specific to anorexia nervosa or bulimia

are actually the result of starvation. These are not limited to food

and weight, but extend to virtually all areas of psychological and

social functioning.

Since many of the symptoms that have been

postulated to cause these disorders may actually result from

under-nutrition, it is absolutely essential that weight be returned to

"normal" levels in order that emotional disturbances may be accurately

assessed.

The profound effects of starvation also illustrate the

tremendous adaptive capacity of the human body and the intense

biological pressure on the organism to maintain a relatively consistent body weight.

This makes complete evolutionary sense. Over the hundreds of thousands

of years of human evolution, a major threat to the survival of the

organism was starvation. If weight had not been carefully modulated and

controlled internally, animals most certainly would simply have died

when food was scarce, or when their interest was captured by countless

other aspects of living. The starvation study illustrates how the human

being becomes more oriented toward food when starved and how other

pursuits important to the survival of the species (e.g. social and

sexual functioning) become subordinate to the primary drive toward food.

One

of the most notable implications of the starvation experiment is that

it provides compelling evidence against the popular notion that body

weight is easily altered if one simply exercises a bit of "will power." It also demonstrates that the body is not simply "reprogrammed" to adjust to a lower weight once it has been achieved. The volunteers' experimental diet was unsuccessful in

overriding their bodies' strong propensity to defend a particular

weight level. One might argue that this is fine as long as a person is

not obese to start with; as we point out later, however, these same

principles seem to apply just as much to those who are naturally heavy

as to those who have always been lean.

It should be emphasized

that following the months of rehabilitation, the Minnesota volunteers

did not skyrocket into obesity. On the average, they gained back their

original weight plus about 10%; then, over the next 6 months, their

weight gradually declined. By the end of the follow-up period, they were

approaching their pre-experiment weight levels.

American RadioWorks has an excellent article on the Minnesota Starvation Experiment here:

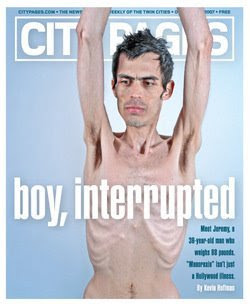

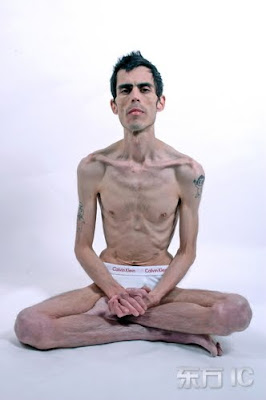

A

half-hour later, Jeremy approached the counter again and dug his hand

into his pocket, plucking out a tiny, folded-up coupon. It entitled him

to a kids' meal—a third the size of an adult sub. Jeremy got a scoop of

tuna fish on wheat, a small milk, a four-ounce yogurt, and a cookie.

A

half-hour later, Jeremy approached the counter again and dug his hand

into his pocket, plucking out a tiny, folded-up coupon. It entitled him

to a kids' meal—a third the size of an adult sub. Jeremy got a scoop of

tuna fish on wheat, a small milk, a four-ounce yogurt, and a cookie. Other celebrities rumored to have suffered from "manorexia" include Ethan Hawke and Billy Bob Thornton (post-Angelina Jolie).

Other celebrities rumored to have suffered from "manorexia" include Ethan Hawke and Billy Bob Thornton (post-Angelina Jolie). "It

serves two purposes," Jeremy says. "It serves a very applied purpose in

that if you're doing the behaviors, you don't have time to think about

being gay. And also being malnourished, you don't feel sexual, so you

don't have to worry about being gay or straight."

"It

serves two purposes," Jeremy says. "It serves a very applied purpose in

that if you're doing the behaviors, you don't have time to think about

being gay. And also being malnourished, you don't feel sexual, so you

don't have to worry about being gay or straight."